Lots of people seem to think that A) government is very inefficient, and that therefore B) we can make society more efficient by cutting the size of government. But actually, (B) doesn't follow from (A). And in fact, the very thing that makes government inefficient in the first place might make cutting it a bad idea!

Why is government inefficient? Because of incentives. Companies generally make hiring and investment decisions based on a marginal cost/marginal benefit calculation (though corporate institutions can of course get in the way of that, and if there are externalities then it's not efficient, etc. etc.). But government makes its decisions based on some other kind of cost-benefit calculation entirely. Sadly, we don't have a good understanding of government decision-making, and this is an area that could use a LOT more research attention than it is getting.

Anyway, because government doesn't make decisions on a monetary cost/benefit margin, it tends to be inefficient. But because of that, if you take a hacksaw to government, starving it of funds or demanding that it fire workers and close divisions, these firing and closing decisions will not be made on a cost/benefit margin. If you force a corporation to downsize, it will usually lay off the least productive workers first. But if you force a government to downsize, it very well might lay off the most productive workers while retaining the least productive ones!

The very thing that makes government inefficient can make cutting government inefficient!

Let's imagine a slightly more concrete example. Suppose that there are three types of government units:

A) Parasites: These units have figured out how to game the political process in order to make themselves quite secure and mostly untouchable, despite the fact that they mostly just extract rents from society without creating any value. They are entrenched vested interests of the type that Mancur Olson talks about.

B) Clunkers: These units are not politically well-connected, but they are inefficient. Maybe bureaucrats or voters thought that these things would be worth doing, but actually they're not.

C) Whiz Kids: These units produce more than what the taxpayer pays for them. Perhaps they are courts that stop crime and protect property rights. Perhaps they are infrastructure agencies that build needed highways. Perhaps they are R&D agencies that do basic research that no company will do. Etc. And suppose they do it for a reasonable price tag.

(If you're either a starry-eyed anarcho-capitalist or someone who likes to spout anti-government rhetoric without thinking about it too hard, maybe you think that category (C) just doesn't exist at all, and that every single thing the government does would be done more efficiently in the absence of government. But you're wrong.)

Now suppose that someone like Grover Norquist comes along and decides to start hacking away at government indiscriminately. Which type of unit will get cut? Not the Parasites, certainly. They're too entrenched. It will be the Clunkers and Whiz Kids that get cut. If there are a lot more Clunkers than Whiz Kids, then this is OK, but if there are more Whiz Kids than Clunkers, then you're in trouble. And either way, cutting government increases the share of the horrible Parasites, and hence their relative power within government.

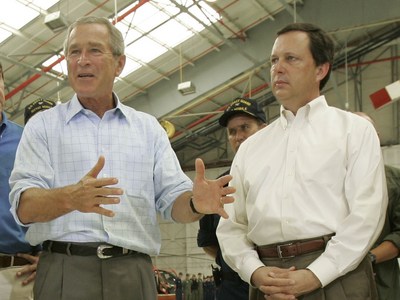

In fact, liberals often argue that this is exactly what happened during the Bush administration. The administration's botched handling of Iraq, Katrina, and other important challenges may be due in part to the administration's excessive belief in the efficiency of limited government. Perhaps instead of thinking about how to indiscriminately cut the size of the government, we should be focusing our efforts on how to tell the difference between efficient government units and inefficient ones, and - most importantly of all - how to excise the nasty Parasites.

I like this analysis. However, what about arguments that cutting government leads to a more efficient *society*, at least in normal times? Assuming we are not at the ZLB, if one cuts government spending, and the fed offsets the cuts with lower interest rates, aren't we then replacing mysterious government utility function spending with efficient private spending? At the very least this affects the ratio of whiz kids to clunkers that would need to be at risk to justify not indiscriminately cutting. I don't consider myself a utilitarian, so this isnt exactly how I conceptualize this problem, but since you argue along utilitarian lines, how does this factor into your analysis?

ReplyDeleteThanks for making this post. It's something I've given a lot of thought to and I think the problem is even more difficult than it appears.

ReplyDeleteGiven that we acknowledge that the government and private sector works with different variables, at the end of the line, say we figure out how to identify and snip the "Parasites," we would still need to convert the units of what the Parasites don't maximize for into the units of what the private sector attempts to maximize for.

This conversion isn't necessarily simple. Even a sub-optimal Parasite might be preventing some amount of market inefficiency in private markets that would otherwise happen through exploitation.

It's a very difficult problem. But beginning this type of dialogue is a good way to acknowledge it.

A) Parasites: These units have figured out how to game the political process in order to make themselves quite secure and mostly untouchable, despite the fact that they mostly just extract rents from society without creating any value. They are entrenched vested interests of the type that Mancur Olson talks about.

ReplyDeleteWell thank god these dont exist in private business!

No, some do exist in business, but it is the result of government poisoning the well from which efficiency and goodness springs. If we could only remove all the laws that create companies, ownership, money, public places to connect all the private places together, and provide an educated workforce to consume all of businesses outputs, then there would be no more parasites in business.

DeleteWhaaat? You want to remove laws? Sounds like a good way to let parasites cheat even more!

Deletebut what business would they be in?

DeleteThanks. Also, in the battle between clunkers and whiz, clunkers are probably doing things that are politically popular and painful to cut, whiz are doing things that have limited immediate short term benefit and therefore, as you say, there is little immediate fall out but long term consequences. Take a look at the current debate in the UK on cuts to river dredging that have exacerbated the flooding.

ReplyDeleteTo be fair dredging would not have stopped the flooding, the real solution is to slow down the water flow, e.g by building wetlands and ponds upstream. The irony is that several such plans were abandoned several years ago.

DeleteLet's assume that you're right, and that a significant number of government employees are "parasites" who produce nothing but cost a lot (I don't agree with that at, but nevermind). Let's also assume that Krugman et. al. are correct that the economy is suffering a lack of demand right now, and that increased government spending would help the economy. In that case, doesn't it stand to reason that firing the parasites would actually hurt the economy by decreasing government spending?

ReplyDeleteIt's not suffering from lack of demand. I have plenty of demand, i demand a huge spaceship and my own castle. I just don't have the money to buy it. Now if only the government is willing to print a trillion dollars and give it to me, i can instant generate enough demand to revive the world economy.

DeleteIf Obama wire 1 trillion dollar to my bank account, i promise i will immediately roll up my sleeve and get to work on generating demand. millions of people will be hired to build my spaceship, my castle will be made of solid gold.

DeleteWhat you describe is not demand. It is want. Demand only exists if there are dollars to back it. Thus, putting people out of work decreases aggregate demand, even if the people put out of work are "parasites".

Delete@meo fio

DeleteGiving you a trillion dollars (presumably through a tax credit) would be stimulative government spending. And yes, that would generate demand, which is needed in our currently depressed economy.

@Anonymous 1

When suggesting we find ways to remove the parasites, I think the author is trying optimize value/returns from government spending. The idea would be to remove the parasites and then employ more whiz kids with the savings and generate more value dollar spent. Removing the parasites and just pocketing the savings would hurt the economy as you suggest in the current Zero Lower Bound environment.

A) Parasites: These units have figured out how to game the political process in order to make themselves quite secure and mostly untouchable, despite the fact that they mostly just extract rents from society without creating any value. They are entrenched vested interests of the type that Mancur Olson talks about.

ReplyDeleteThis does not just happen in the public sector. Think about Goldman Sachs or the Freshwater School in Macroeconomics.

In the early 80s I worked for a company that needed EPA approval to market newly developed products. Along came Reagan to cut the EPA budget to "get the regulators off our backs". The workers who reviewed the regulations were cut. We had fewer people to review our applications and the process took longer. Incompetent managers lead to incompetent government.

ReplyDeleteThe scenario that you describe sounds more like underfunding/understaffing than incompetent managers.

DeleteI think the first Anonymous poster was suggesting Raegan was an incompetent manager. The incompetent manager made the decision to understaff and underfund the EPA.

DeleteI like the message of this post.

ReplyDelete-Government is so inefficient that we shouldn't cut government

It is something that I too have been thinking about, however (seems like lots of people have). Politicians obsessed with shrinking the state tend to think that a smaller state is good under all circumstances and therefore any cut is worthwhile. This leads them to start by cutting the parts that are easy to cut rather than the parts that truly are inefficient.

[I like the message of this post.

Delete-Government is so inefficient that we shouldn't cut governmen] x 2

Not because I agree with the message, but because it clearly shows how much ground the left has ceded to critics of libertarian and public choice theory persuasion, since the halcyon days of Galbraith and Paul "Soviet Union will be richer than America" Samuelson.

This post by Noah Smith remembers me of this post by Caplan about Paul Krugman.

http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2004/07/paul_krugman_gu.html

I'm confused as to why you would connect the "soviet union will be richer than america" quote to halcyon days. Clearly, Samuelson was talking rubbish.

DeleteAs for the rest:

Right now, Paul Krugman, Noah Smith(and other american 'left-wing' economists) have very sensible, reality-based ideas about how to improve things. Sure this is a sign that the overall balance has shifted too far to the right but it's refreshing to have a political body almost exclusively filled with good ideas.

Contrast this to the early post-war period where democrats and republicans were both right about some things.

"Halcyon days" was an ironic reference. All that I'm saying is: mainstream economists from the left used to have rubbish ideas like these. After unrelentless strafing fire from the likes of Milton Friedman, the fall of planned economies, etc., they've learned the hard way to be lot more reasonable.

DeleteTake Noah Smith: he cannot say, like the leftists from previous generations used to, that government is a great way of providing public goods and resolving externalities like pollution. It is a possible way, sure, but with a lot of problems of itself to lend it the credibility that leftists of yore granted to it. Like Caplan said: "At least in economics, the intellectual climate hasn’t been as good [i.e. "libertarian" or "classically liberal"] as it is now for a century." America has domesticated their PINKOs. They are fluffy and cute nowadays -- as Noah Smith shows with this post -- not like they were, say, in the sixties/seventies/eighties.

Art Okun would likely be underwhelmed by this piece.

ReplyDeleteThe starry-eyed social democrats keep trying though.

Also, assuming there are indeed laws in macroeconomics (contestable), then most of the time, above certain annual outlay thresholds, larger government is associated with slower GDP growth:

Deletehttp://www.ifn.se/wfiles/wp/wp858.pdf

Even after reading the last paragraph it is not obvious to me what Bush has to do with budget cutting or limited government. And before we assign Katrina's handling to limited government, shouldn't we first look at whether FEMA's personnel budget was actually cut? I looked at the FY2002 proposed budget (http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BUDGET-2002-BUD/pdf/BUDGET-2002-BUD.pdf) and the administration in fact did propose cuts for FEMA, but these were for subsidized flood insurance, which strikes me as a good thing and it's not apparent how that would impact its response to Katrina. Also, given that Bush rode into office promising more help for the military, it is unclear how limited government or budget cuts related to Iraq. Seems to be a lot of conjecture here without much in the way of evidence.

ReplyDeleteAa ha, this is indeed an interesting subject to discuss. Well, it's not because government is inefficient; rather the public, owing to whatever reasons, have an utopia expectations of government.

ReplyDelete1) Take California during the Governator years, when during campaigning, promised to weed out all the efficiencies particularly unnecessary government departments/functions. It's no coincidence that he could barely (or not) find any 'excesses' once he begun His Rule, as every single government departments has its duties and obligations.

There cannot be any cost/benefit solution to government; unless it's agreeable that a poor patient should choose his prescribed medicines to save cost rather than to take all which is recommended by the doctor!

2) Time to tackle the incentives argument; i always equate government to Microsoft. Microsoft is an extremely profitable behemoth, yet often being criticized for missing the trend or losing opportunities or even headed to extinction owing to (un)visionary board members. Despite all these, Microsoft has been making gazillions annually, making shareholders and investors happy (mostly); and a new successful product every decade! . Now imagine if Microsoft becomes very reactive, or more proactive, or always wanting to be at the frontline; the possibility of not making the existing billions would not only put the board at jeopardy, but it's employees, shareholders, and even the average users and non-users! The risk of default is real.

*Do note that Microsoft directors and senior employees sit in boards of successful ventures

The government is in a similar position; as it's a monopoly by itself. A monopoly of procurements, licensing, and pork-barreling. The government works on incentives, which is its survival! A decade or two may be a long time for an individual, but not for the government.

3) Finally, the parasites, clunkers, and whiz-kids are improperly defined. In actual fact, the parasites are the bureaucracy itself - which means that it consists mainly of ivy league and/or sons & daughters of the wealthiest/smartest families. The clunkers are the consultants - like those listed in the fortune 500! Finally, the Whiz-kids are the elected officials and the political aides. Thus reducing budget meant more pain for those elected, causing only the self sustaining to run for office; and reduce political aides, meaning the elected official is as knowledgable as he/she can afford to be.

So does cutting government make it more efficient? Well, it depends on what the individual wants. Just like in any corporation, does the employee want more authority, better benefits, higher salary, unexpected bonuses, personal time, no disturbance from bosses etc when comparing to his peers. The corporation weighs the interest of its owners/shareholders, management, and the employees. The Government is no different.

1. GWB GREW GOVERNMENT (in salaries and headcount) far more than an other modern President. That's his greatest personal failure - as a very smart MBA (top poker player at Harvard) he was well versed in productivity gains justify smaller higher paid workforces.

ReplyDelete2. Sequestration proves this thesis wrong. Obama very likely has delivered the only 1%+ productivity gains at Federal level since early 90's.

3. If you look at the actual work of Blloomberg (Steven Goldsmith) and Indiana (Steven Goldsmith), and the correct methodology to cutting government is NOT FIRING.

It's is attrition. You establish a "second higher tech track" a parallel to the current way government is run, and then slow down and improve hiring, and overtime let the parasites be removed by nature.

There is a correct middle ground here, it's less painful and less efficient than changes in corporate world, but that's ok. But still government becoming more efficient can and does happen.

Actually I thought the argument against the Bush admin was that they were parasites who figured out how to game the system help help their crony friends in the defense department and oil industry. govt most certainly did not shrink during the Bush era, it grew to include a much larger national security apparatus and gazillion $ wars.

ReplyDeleteThe incentives and cost/benefit calculations for political agencies are pretty well known: Help your boss get re-elected. Hire someone from a group that donated a lot of money, put your friends on a board, and so on.

Corporate executives are parasites as well. The difference is that (most) companies align parasitic incentives with the bottom line. In some companies, incentives are aligned to keep the boss in power, same as in politics. The less a company has to worry about profits, like Fannie and Freddie, the less the corporate incentives are aligned with profits and the more they are aligned with politics. Corporate boards can be stacked to protect management.

Also, you left out: government, like utilities, is inefficient because they are monopolies. A monopoly will deliver inferior goods (lower Q, which can be interpreted either as lower quality or fewer goods, or both) as a consequence of a perfectly rational profit motive, maximizing profits.

"But government makes its decisions based on some other kind of cost-benefit calculation entirely. Sadly, we don't have a good understanding of government decision-making, and this is an area that could use a LOT more research attention than it is getting."

ReplyDeleteNo doubt there's plenty to be said for bureaucratic budget maximization, regulatory capture, and other theories about the incentives for government decision-makers. But, when trying to understand government programs, a good place to start is always with the _authorizing laws_. For example, in the Am Trucking Assoc. case, the S. Court concluded that the Clean Air Act unambiguously barred EPA from considering costs in reducing risks to ambient air pollutants. Not exactly a recipe for efficiency, eh? Also, compare the relatively simple objective function of a profit-maximizing firm to the multiple, ambiguous, and competing objectives specified by statutes. What's the optimal balance between security and privacy? In many statutes, Congress essentially delegates the politically intractable and incalculable tradeoffs to agencies. What's the optimal balance between impinging the current profitability of financial firms versus reducing by an uncertain degree the risk of a 1 in 50 year financial meltdown? Finally, many gov't programs essentially insure the uninsurable. An alternative question is why should we presume that efficiency is the aim of gov't?

I agree with everything here except the notion "If you force a corporation to downsize, it will usually lay off the least productive workers first." You clearly have not worked for a Fortune 100 company during a downsizing.

ReplyDelete"The administration's botched handling of Iraq, Katrina, and other important challenges may be due in part to the administration's excessive belief in the efficiency of limited government."

ReplyDeletePerhaps, but it seems more likely that it was due to the conviction that competence doesn't matter in government (it's all so easy?), just political loyalty. That's why FEMA was staffed by people with no experience (in stark contrast with the Clinton years) and managers in Iraq were all people who had posted resumes at right wing web sites.

I think this statement requires modification based on my anecdotal observations:

ReplyDelete"If you force a corporation to downsize, it will usually lay off the least productive workers first. "

With large corporations, they will tend to trim departments that are less profitable and cost centers.

I have rarely seen this translate into laying off the least productive workers unless there was a lot of latitude granted to the first-line managers in selecting candidates, those managers were good managers, and the reduction goal was somewhat flexible.

More often I have witnessed people being slated for reductions when only months before they were granted huge bonus awards for their outstanding accomplishments.

So... like government, large corporations can be somewhat arbitrary too, at least in terms of how worker productivity plays a role in staffing decisions when cost-cutting is the primary goal.

Nothing like seeing somebody get 100K in stock options for their contribution and then get walking papers less than 6 months later to wake you up to that. You wind up understanding that no matter how hard you work, no matter how much it is recognized as valuable by your peers and management, your future in your present job is somewhat uncertain and subject to the vagaries of broader trends and objectives when do not translate especially well into actual implementations.

Oh, I thought of an example where effective first-line management won't help you too:

DeleteWhen it conflicts with the manager's own self-interest.

Example: let's say you have a department of 10 people, and the top two producers make twice as much as the median worker, and they make 3 times as much as the bottom 6 producers.

Objective: reduce costs by 50%.

Manager's incentive: if staff is too small, they will combine departments and fire me.

Solution: Keep one top producer (to keep things going), fire one, etc--get the magic 50% without making staff too small.

They say they will cut the fat, not the bone, but it's the fat that makes the cuts.

ReplyDeleteI love this post, Noah.

ReplyDeleteThis discussion reminds me of teachers unions. Typically, a teachers union requires that when budget cuts sweep through a state or district. new hires are laid off first. Why? Because in the teaching industry, salary is commensurate with experience; the fear is that administrators will simply default to removing the most expensive faculty.

One problem with this view is that it's fundamentally wrong that teachers aren't paid based on competence. In fact, teaching is one part of government where we actually have good or improving data on student performance (or growth in performance).

I wonder if such accountability can be extended to other high-stakes area of government.

LOL Meritocracy is an Ideal. What it isn't is a reality in any large organization where I have been a member, and I have worked almost exclusively in the private sector.

DeleteIt's another Unicorn. Most of the broad-sweeping generalizations that dance across peoples' minds and stumble out across their keyboard or out of their mouths on this topic are wishful thinking.

It's not entirely clear that government does not make decisions on a benefit-cost margin. It could be certainly argued that it does at least some of the time. Industry, on the other hand, does not necessarily always make decisions on those margins, either. The same categories into which you decomposed government could likely be delineated inside of firms as well.

ReplyDeleteBut do you really think that working at a private firm or organization implies added value? My guesstimate is that 75% of our income depends on (small) politics. The other 25% produces what is necessary for all of us. The rest is, more o less, politics.

ReplyDeleteCutting government may be the efficient thing to do if the whiz kids the government lets go of "inefficiently" from their standpoint end up in jobs where they are more productive than they were in government.

ReplyDelete"may" is the key word here. As Noah pointed out, some wiz-types are needed.

DeleteAnother complicated issue here that I do not know how to fit clearly into this story is that often when there is cutting and public staff reductions, the functions those people were doing, which turn out not to have been purely parasitic but actually needed end up getting outsourced, often at much higher cost for the same servive, with the employees getting paid multiples of what the former public employees were. These private contractors may or may not be more productive in terms of their output per time, but they have often proven to be out of control or creating extra problems.

ReplyDeleteThe obvious case here is the outsourcing of the setting up of the ACA exchanges, which ended up going to a firm that had a documented record of outright incompetence on such matters, and proceeded to prove it yet again.

Another example involves a lot of national security stuff. We have private contracters doing very supersecret stuff for NSA, leading to Snowden, although he may have done us all a public service. We had firms in Iraq that were running around killing civilians and creating diplomatic problems, with those guys definitely being paid far more than regular soldiers. And then we have the botch of private contracters guarding embassies rather than Marines. Well, I am not going to go on about that one. But, I can say that a major reason Northern Virginia has some of the highest income jurisdictions in the nations is that this is where a lot of these outfits and their employees are based.

Barkley Rosser

Interesting idea with the modifications to the gov't group types. However it misses the key failing of the 'business is efficient, government is inefficient mantra'. The idea hinges on two basic concepts, government suffers from both diseconomies of scale (caused by being too large) and x-inefficiencies (caused by the lack of competition). Working ofr a consultancy firm that is paid by public and private sector we see advice that we think is good and will reduce x-inefficiencies routinely ignored by both public sector and large oligopolistic private sector firms (say hi, Big 4 audit firms). In both cases, the advice may have been wrong but they happily paid for our time before ignoring it and carrying on as before, so x-inefficiency occurs in both public and private sector. As Coase showed, firms only exist where it is inefficient to transact with other human beings using markets. Thus firms have no internal mechanism to be efficient (unless you work in a business where the VP of marketing must buy time with the Financial Controller in order to agree a budget and then sell their plan to the board) and without genuine competiton there is no external impetus either. Therefore government failure is simply an alternative to market failure.

ReplyDeleteBut if you admit there are efficient parts of the government (which every elected official believes but half will not say), then you get in the way of the real goal: cutting rich people's taxes.

ReplyDeleteHow can I promise my big donors more tax cuts if I'm busy saying that we need to fund the CDC or the NIH (both of which should be unequivocally in the good category)?

The object isn't to make government more efficient. That is an impossibility. The object is to make government less intrusive. Less government means less meddling. Which makes private citizens and their business more efficient.

ReplyDeleteIt comes down to this: Do people want government to take a lot of their money to waste on inefficiencies, fraud, & abuse, or would they rather government take less of their money to waste on those things?

ReplyDeleteThe discouraging thing here is that Noah is postulating this as a theoretical possibility rather than rely on actual knowledge of how the federal (or other) governments work. Given the degree to which public policy depends on that knowledge, you would think such knowledge would be a prerequisite for public discussion. In fact, on the ground reporting of how agencies actually work is vanishingly rare.

ReplyDeleteIn fact, on the ground reporting of how agencies actually work is vanishingly rare.

DeleteDidn't I point this out early in my post? ;-)

Yes you did. I missed it. I think I was hoping that there would be some cultural knowledge of government among economists based on direct experience. However most economists who have any experience in government seem to have been so high up eg CEA, that they seem to have little idea what is really going on. I work on front lines in a non-glamorous agency and am constantly frustrated by rules established by OMB that have no relationship to reality, an HR process that is designed to fail, marginal IT support, etc. On the other hand, there are professionals there that make the agency work much better than one could expect. So I am suggesting go out and find out! Make a great PhD project for someone to look at these problems from an economist's perspective. Only problem is current employees can get fired for talking about bad management. As opposed to activities protected under whistle blower protection. We are just talking mediocrity not criminal activity.

DeleteNoah,

ReplyDeleteI'm afraid I disagree with your entire premise. Governments DO make decisions based upon a marginal cost/marginal benefit calculation. It's just that the benefit may be measured in social rather than monetary value. (It may also be measured in political value, but arguably that's corruption.)

In project finance, this would be justifying a project on the basis of intangible benefits. As a project manager I always tried to avoid doing this, but some private sector projects can be amazingly difficult to justify on tangible benefits alone - except for Finance projects, whose owners seem to be able to identify tangible benefits for the most fanciful schemes. Oh to be a real accountant.

I suspect that in the public sector there are simply far more investment decisions justified partly or entirely on intangible benefits - improved social outcomes that are difficult to quantify. Once you are in the habit of justifying investment decisions on intangible benefits, decision-making tends to be somewhat flimsier, simply because it's difficult to compare real costs with intangible benefits. But they should at least attempt to quantify the benefits.

The trouble is that particularly in areas such as social service and healthcare, attempts to introduce this sort of financial discipline can be seen as heartless. We have seen this in the UK with arguments about whether the social benefit of keeping very premature babies alive (who will probably end up severely disabled) justifies the cost. It doesn't, frankly - but who is going to say that to the parents of a 24-weeker who is just clinging on to life?

Why did you capitalize the word "finance"?

DeleteHabit.

DeleteThis post is a nice example of the excessively high level thinking of economists about government I mentioned above. Noah's post concerned cutbacks and where they occur in agencies and effect on outcome. It started to come closer to the real chaos of actual life. So when cutbacks occur is government better or worse in selecting even socially rather than economically driven goals?

DeleteBased on the Obamacare website debacle among many others, it seems as if it is common for leaders of agencies to have limited idea what their agency actually is doing.

I think more attention needs to be placed on that concept rather than fine distinctions between economic and social goals.

I'm not making a "fine distinction between economic and social goals". Nor am I indulging in "excessively high level thinking". Quite the reverse, actually. I'm looking at this at an entirely practical level.

DeleteThe process of justifying investment spending in both the public and private sectors is pretty much the same. It is the definition of benefits that differs. The public sector tends to measure benefits in terms of social outcomes, whereas the private sector tends to measure benefits in terms of financial gain. My point was that justification of spending on social grounds is not necessarily inefficient, just extremely difficult to quantify. The prevalent belief government is inevitably inefficient because its spending decisions are socially rather than financially motivated is simply wrong.

All large organisations suffer from agency problems. How many CEOs of large private companies have any real idea what goes on at lower levels in their organisations?

You are still not addressing the point of Noah's post. And you missed my point entirely. You are claiming that there is a rational basis in agency actions which favors social utility as opposed to economic return. As a generalization, that is probably true as an ideal for some agencies (justice, education, HHS) and not others (commerce, treasury). I think that Noah is positing that agencies may sometimes not use any overtly rational overall external goal but are primarily subject to internal politics especially when confronted with reduced resources. I was suggesting that agency heads are particularly unlikely to overcome this internal political struggle as they have limited understanding of their agency.

DeleteYes the private sector has the same overall problem of leaders not really knowing what is going on (see the banks pre-2007). But that is not what we are talking about here.

The idea of conflict between the professional and political staff is not novel. Nor is the concept that management may be more internally than externally motivated. What we need is better understanding of the process.

FYI, I am making these points in an attempt to improve government, not dismantle it.

Keep in mind too that a business can exclude classes of people that it does not want as customers; if a customer is expensive to service private firms simply walk away from them where government is mandated to provde services which is a very different activity driver. Don't be surprised to find a wide range of effectiveness in government, what I look forward to is seeing how you weight the simple, uncostly service vs the complex required service. A simple cost comparison by head count for example is supremely misleading in many government programs

ReplyDeleteSaying "incentives matter" really means nothing at all. The mere incentive of profits does not drive people towards becoming more efficient. It is competition for profits that matters. That is a critical distinction when speaking about relative efficiency in the "private" and "public" sector. Simple example: if I had a monopoly in the restaurant business in a town and then another restaurant opens and challenges my dominance, the response will be based on how I can deal with the competition. The cheapest way to end the threat would be buy matches and burn the other restaurant down, not to make my business more efficient, which means altering my operations and a lot of other actions that might be disruptive. Fear of retribution (by the other owner, or the State) is what would likely prevent that action. The public sector can be very efficient on issues where interstate competition is involved - just look at how much more efficient at blowing things up the public sector has become over time.

ReplyDelete"Government efficiency" becomes an issue when competitive pressures are unlikely, including when trying to provide a good competitively would be inherently more inefficient than a single system. In those cases, competition within the public sector (ie, the fact of elections, or the threat of a coup) is what keeps governments on their toes. The public sector is much more efficient at policing today than before, because each government has the incentive to improve efficiency to remain the government and not be voted out.

The biggest single real problem with making statements about public sector efficiency is that ANY measure of efficiency can only work if you have an accurate means to measure input and outputs. How do you measure the "efficiency" of a child welfare system? Number of kids placed in new homes? Number of abused kids? Number of fatalities? How many abused kids is one dead kid worth? It seems to me the biggest controversies in "government efficiency" come in areas where quantifying success is contentious to begin with.

Koan: If you believe government is unfit to allocate investment, why do you think it is fit to deallocate it?

ReplyDelete