"I was on top of the Westin Hotel being shown the sights of [Shanghai], and I had a sudden crisis as I looked out at the extraordinary skyscrapers the architecture and the art deco. I thought to myself, well, the mandate of heaven has passed from us and come home." - Gore Vidal, 2007

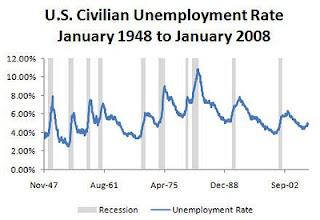

I'll say this about Tyler Cowen's

Great Stagnation hypothesis: it has really made me think. Although I was resistant to it at first, the more I look at the evidence, the more compelling it seems. Income growth in the U.S. really has slowed down since the 1960s, and more recently, in all the rich countries.

Cowen's idea has much to recommend it. It's undeniable that the easy gains from universal public education and exploitation of cheap land are over. And it also seems pretty clear that there has been a stagnation in transportation technology since the mid-century, driven by the

plateauing efficiency of our energy sources. There's a reason our innovation has switched from stuff like cars and planes to stuff like computers and phones.

On the other hand, the idea that our stagnation is driven by exogenous changes in scientific discovery - we just didn't find enough new stuff this half-century! -

does not sit easily with me. One reason for this is that I have a very hard time believing that changes in the rate of technological progress could cause a decrease in per-capita incomes. Consider this graph of real working-age household income since 1987 (courtesy of

Karl Smith):

I just have a hard time believing that a slowdown in scientific discovery could cause incomes to go down. I mean, technology doesn't get worse over time, right? (This is also one of the big problems that everyone has with RBC models.) I mean, mayyyyybe technology could stagnate so much that we hit a Malthusian ceiling, in which population growth increases resource costs to the point where people start getting poorer. But it just seems unlikely.

Therefore, I have been thinking about alternative theories to explain rich-world income stagnation. And I have come up with something. I call it the "Great Relocation". The idea, in a nutshell, is that economic activity is relocating from rich Europe, America, and Asia to developing Asia faster than technological progress can replenish it.

The idea of how this works is not due to me, but to Paul Krugman.

Economic Agglomeration and the New Economic Geography

In 2008, Paul Krugman won the Nobel Prize, in part for a theory that called

the New Economic Geography. That also happens to be the first economic theory I ever learned in detail (back in 2004!), and the one that lured me into the field of economics. It's a brilliant idea, and has some solid

empirical support. You should

read about it, if you don't mind a little math.

The basic idea of the theory is this: It is expensive to move products around. This means that if you have a factory, you want to locate it close to where your customers are, to avoid paying a bunch of shipping costs. Now consider two factories. The workers in the first factory will be the consumers for the second factory, and vice versa. So the two factories want to locate near each other ("agglomeration"). As for the workers/consumers, they want to go where the jobs are, so they move near the factories. Result: a city. The world becomes divided into an industrial "Core" and a much poorer agricultural "Periphery" that produces food, energy, and minerals for the Core.

Now when you have different countries, the situation gets more interesting. Capital can flow relatively easily across borders (i.e. you can put your factory anywhere you like), but labor cannot. If you start with a world where everyone's a farmer, agglomeration starts in one country, but that country gets maxed out when the costs of density (high land prices) start to cancel out the effect of agglomeration. As transport costs fall and the economy grows, the industrial Core spreads from country to country. Often this spread is quite abrupt, resulting in successive "growth miracles" that get faster and faster (as each new industrial region starts out with a bigger global customer base). The

evidence strongly indicates that agglomeration is the driver behind developing-world growth.

But here's the thing: in the theory, the "old Core" doesn't keep getting richer. In fact, under some scenarios (which are difficult to explain concisely), the old Core even gets slightly poorer while the "new Core" catches up. For a while, the negative effects of relocation trump the positive effects of progress.

So this could explain why people in the rich world are getting poorer. In the 50s, America was the only industrial "Core" on the planet. But since the 60s, we have seen successive "growth miracles": Japan and Europe in the 60s/70s, then Taiwan/Korea/Singapore in the 80s, then China since then, and now even India. In a New Economic Geography world, we would expect these successive relocations of manufacturing to hold down income growth in the U.S., even if technology was advancing as usual. And now Japan and Europe are feeling the pinch as well.

Core and Periphery

But the problem is especially acute for America, and here's why. Let's think about Cores and Peripheries. Take a look at this population density map of the world:

Suppose all of those people had the same purchasing power. If you were a factory owner, and you wanted to minimize transport costs, where would you put your factories? The answer is a no-brainer: China and India. Some others in Europe, Japan, and Indonesia. Perhaps a couple on the U.S. East Coast. But for the most part, you'd laugh in the face of any consultant who told you to put a factory in the U.S. The place looks like one giant farm!

It may be that American manufacturing strength was due to a historical accident. Here is the story I'm thinking of. First, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, our proximity to Europe - at that time the only agglomerated Core in the world - allowed us to serve as a low-cost manufacturing base. Then, after World War 2, the U.S. was the only rich capitalist economy not in ruins, so we became the new Core. But as Europe and Japan recovered, our lack of population density made our manufacturing dominance short-lived.

Now, with China finally free of its communist constraints, economic activity is reverting to where it ought to be. More and more, you hear about companies relocating to China not for the cheap labor, but because of the huge domestic market. This is exactly the New Economic Geography in action.

Sustain Points and the Great Recession

Actually, the story could be even worse for us. There is another interesting feature of the New Economic Geography theory: hysteresis. I.e., history matters. A place that becomes a city will not easily turn back into a farm. There is a "sustain point" in the economic forces that make an agglomeration viable, and as long as a Core region stays above that point, its initial good luck in becoming the Core will keep it safe from turning back into a backwater.

BUT, a severe shock can knock you down below the sustain point. If your Core no longer has a good reason to be the Core - if it remained rich and built-up only because it would have cost too much to move it - then a big recession (or a devastating war, or a natural disaster) will cause economic activity to leave permanently. Think about the permanent shrinkage of New Orleans in the wake of Katrina.

In this light, the Great Recession of 2008-whenever might be a lot more ominous than even the Great Depression. What if this gargantuan shock has finally made it worthwhile for the center of world industrial activity to relocate to the North China Plain, where nature says it ought to reside?

In that worst-case scenario, the U.S. industrial economy is not coming back any time soon. From the air we look like a farm, and that is what we will once again become. Thanks to our technological edge, we will retain strengths in industries like software and business services, for which transport costs are extremely low. But our days of "good jobs for everybody" are done. (Keep in mind, this is just a worst-case hypothetical.)

Relocation and Stagnation

Note that although this Great Relocation is an alternative to Tyler Cowen's Great Stagnation, it does not preclude it. Lower productvity growth could coexist alongside agglomeration effects. Or...they might even go together. As I

wrote in an earlier post, some "endogenous growth" theories suggest that the availability of cheap labor can reduce the incentives for innovation. If technological progress has stalled, it might just be because the Great Relocation has taken priority.

So What Do We Do About It?

So China "took our jobs." But this was not due to their exchange rate policy, or their export subsidies, or their willingness to pollute their rivers and abuse their workers, although all these things probably spend the transition. They took our jobs because it made no sense for a farm like the U.S. to be building the world's cars and fridges in the first place. Forcing China to revalue the yuan might slow the Great Relocation a little, but has zero hope of stopping it.

So how do we fight this force of nature? How do we get new jobs? I have a few ideas, but keep in mind that these are the thoughts of Smith, not Krugman, and thus take them with a couple extra grains of salt.

1. Keep immigration going strong.

The United States still has a massive technological and institutional edge. That means that people who come here will be more productive than Chinese people for a long time to come. Every worker we add increases local demand by a lot, and decreases the incentive for production to relocate. This goes double (or triple, or quadruple) for high-skilled immigrants. Beefing up our population with the world's elite knowledge workers is pretty much a no-brainer.

Canada gets this; we do not.

And in the long term - a few decades down the line - high immigration levels will even

reverse the Great Relocation, if

China's population ages dramatically and ours remains young and growing. With our fertility at exactly the replacement level, the U.S. will only grow by immigration.

2. Promote urban density.

Agglomeration happens because people live close to one another. But the United States has some of the world's least-dense cities, thanks to massive zoning and building height restrictions (and free parking). If darker purple on the "density map" equals long-term prosperity, we need to scrap these policies and start encouraging high-density housing and efficient light rail systems. We need a place to put all those new, high-skilled immigrants!

This will require conservatives to

give up their nonsensical anti-train animus. It will also require certain well-off liberals to drop their NIMBY-ish insistence on "open space" (I'm looking at you, Silicon Valley!). Most importantly, because new immigrants will come mostly from Asia, this will require Americans of all stripes to reconcile themselves permanently to the notion that they live in a multi-racial country.

3. Repair the roads, now.

Agglomeration depends not only on density but on transportation costs. Lower transportation costs between cities make it easier to transport goods between cities. If we make it cheaper for California and Michigan to supply each other, it strengthens the status of the United States as a single industrial agglomeration.

Our roads here in America used to be the world's best, but now

they are falling apart for lack of maintenance. This needs to change, and now - while borrowing costs are at rock bottom - is

exactly the time to do it. Note that public goods spending is also believed to be the most effective kind of stimulus...so this is a case in which there is zero conflict between short-term and long-term priorities.

4. Conclude free trade deals with other rich countries.

The Great Relocation story is about the world's industrial Core shifting to poor countries in Asia. This may cause some to agitate for trade protectionism (though I think this could only slow the transition, and probably at great cost). But it makes lots of sense for us to boost our trade with other rich countries - i.e., the other countries of the Old Core. Production is not going to relocate from the U.S. to Japan or Europe, because costs there are equally high. Instead, what will happen is closer to the standard "comparative advantage" or "New Trade" stories, where both countries get a boost. (Another way of thinking about this is that free trade lets us improve our competitive position vis-a-vis China when selling stuff to Europe and rich Asia.)

There is one such agreement currently on the table: the Korea-US Free Trade Agreement. Korea is a rich, developed country, so we should pass this right away.

(Update: I removed a fifth suggestion, "support basic research," since I am kind of a broken record on that one anyway, and it's not really agglomeration-related.)

So those are my policy suggestions for fighting a Great Relocation. Keep in mind that these things are almost certainly good things to do no matter what. But in a world where the U.S. is in danger of turning back into a farm, these measures become essential.

Also, note that the Great Relocation is a story about the long term, not the short term. These are not policies to fight the current recession; they are policies to increase the growth of U.S. median income over the next 20 to 50 years.

Anyway, there is my alternative to the Great Stagnation story. My story is equally scary, but it is something that policy can address. I am not certain that this is really what is going on, but I think it it is worth a lot of thought, and some research too.

OK, back to dissertation. :)

Update: Ryan Avent writes:

It's not clear what story Mr Smith is telling.

Let me boil it down. There are two stories here:

Basic story: Rich countries are experiencing a temporary and mild drop in living standards as China and other poor countries go through an ultra-rapid transition from farming to industrialization.

Scarier story: With the entry of East and South Asia into the global trading system, the U.S. will be in the "agglomeration shadow" of the new pattern, and hence will (partially) deindustrialize. This transition was hastened by the shock of the Great Recession.

I'm not saying either story is definitely true; I don't have the empirical work to make a definitive statement. The basic story sounds very plausible to me, and the scarier story sounds less likely but very scary. My point is agglomeration is a big idea and nobody so far has been talking about it much when they talk about developed-world income stagnation.

Update 2: The Economist has some data that seem to support this general story I'm telling. Thanks to commenter "notyourbusiness" for the link.