Thirtysomethings like myself - the leading edge of the Millennial generation - often speak with reverent nostalgia of the 1990s. We make

. Twentysomethings - the younger Millennials - are confused by this. What made the 90s so amazing?

I want to explain.

In many or even most ways, life is better now than it was then. We have smartphones - supercomputers in our pocket! In the 90s we didn't even have cell phones. We have social networks now - in the 1990s you had to keep in touch with old friends by email. We have GPS and digital cameras and YouTube and Yelp. Society is better now too. We have gay marriage now - that was a pipe dream in the 90s. So was a black president.

What did we have? We had expectations.

The world of the 1990s wasn't the best world in history. But for Americans, it was improving at a

faster rate than at almost any other time. And when the world is improving at a rapid rate, we often expect it to continue doing so. Those great expectations - which economists call "

extrapolative expectations" - contribute a lot to our

happiness. The shining future becomes a kind of wealth, and everyone feels rich.

Here are some of the ways that the world changed for the better in the 90s.

Geopolitics

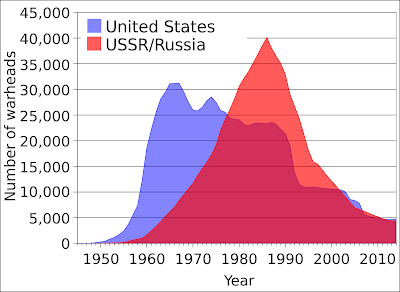

As crazy as this sounds, I grew up thinking that the human race didn't have long to live. When I was a little kid in the 1980s, my parents told me that there would probably, at some point, be a third world war. The U.S. and Soviet Union would nuke each other, and human civilization would fall. This was presented as the most likely possibility - the only way for us to survive was to remain forever balanced on the knife-edge of Mutually Assured Destruction. The USSR was teetering economically, but everyone said it would never fall without launching its nukes in a final bitter gesture, like Hitler ordering all-out attacks in the last days of World War 2.

And that would be the end of us all. Look how many nukes there were in those days!

Nowadays a U.S.-Russia nuclear exchange would mean the end of both of our countries. In 1989, it would have meant the end of human civilization.

Then one day I woke up in August of 1991, and I heard the radio in my parents' bedroom. They never turned on that radio, so I knew it was important. I asked my mom what was happening, and she told me that the Soviet Union had just fallen. Actually it was just a coup - the fall came somewhat later. But in that moment I knew. There would be no bitter, final world-destroying gesture. We would live on.

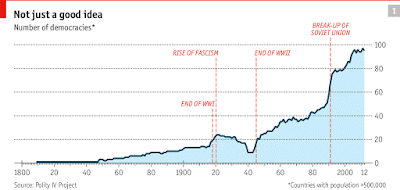

Starting at the end of the 1980s, freedom and democracy - and American power - spread across the globe:

Technology

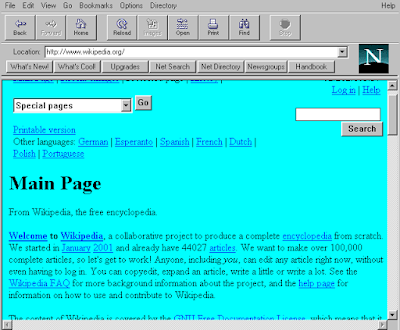

The 1990s saw the explosion of information technology. In the 80s we got personal computers, but in the 90s we got Windows, then email and Usenet and IRC, then - finally - the big one.

Netscape.

At the beginning of 1994, if you wanted to find out a fact, you looked in a paper encyclopedia, or went to a library, or asked the nearest wise-seeming human being. If you wanted to talk to someone in another country, you signed up for a pen pal service (though Usenet and IRC were already chipping away at that barrier).

In late 1994, if you wanted to do either of those things, you clicked on a little blue "N" icon, and suddenly this magical window opened, and you could talk to people in India, or read about how quantum mechanics worked, or learn how to get in shape, or get ideas for Dungeons and Dragons campaigns, or see what naked people looked like, or make fun of X-Files fans in real time. It was like going to college or moving to a big city, but for everyone. The world just exploded. It's impossible to describe the change. It was like adding another dimension to the Universe, and finding that you had been living in Flatland all along.

Of course, a steady stream of internet services followed - online shopping, chat, payments, games, maps, better search, video, video chat, etc. etc., and finally social media. But in 1994, as soon as that magic window appeared, it was clear that all of that stuff was on the way, and soon.

Social Progress

One of the most remarkable and wonderful changes in the 1990s was the progress of gender equality. In 1980, a minority of women were working outside the home in the U.S. - by 1985, it was a majority, and by 2000 it was over 57 percent:

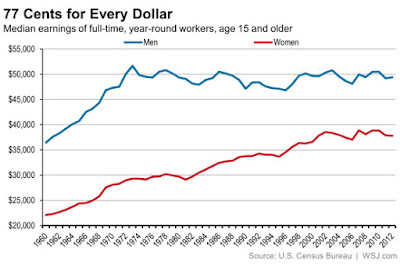

The gender pay gap for men and women also steadily shrank during the 80s and 90s, reflecting both

more equal pay for equal work

and more promotion and hiring of women to higher-paying positions:

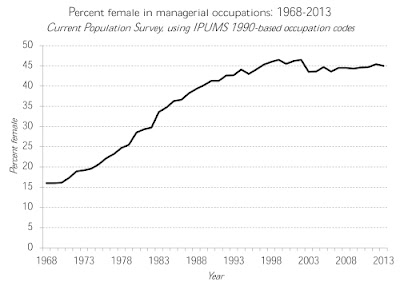

The percentage of woman managers also

increased dramatically:

Women also took a steadily higher percent of professional jobs.

Now, the gaps between men and women didn't close in the 80s and 90s. But they shrank a lot. And remember, the key to understanding the 90s is optimism. We thought those gains would continue. (Sadly, they did not.)

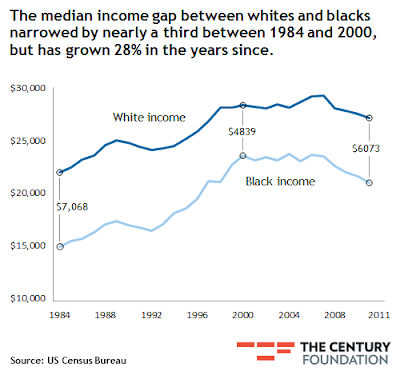

Race relations also seemed to be improving in the 90s, after the disasters of the 80s. Positive attitudes toward interracial marriage

jumped. The black-white income gap was cut

by about a third between 1992 and 2000:

Again, these were gains we thought would continue (but which sadly did not).

Health and Crime

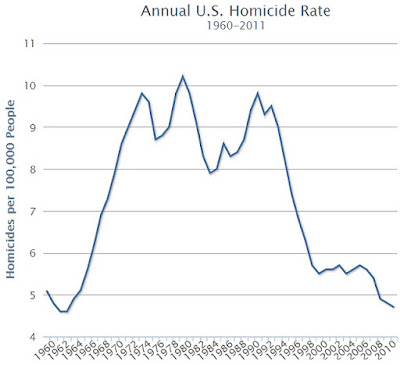

The 1980s and early 90s saw an enormous crime wave. Everyone knew victims and perpetrators. Cities were anarchistic no-go zones. My cohort had one of the highest teen murder rates in the country.

Then, suddenly, crime dropped off a cliff. In a few short years, the murder rate dropped to levels not seen since the golden years of the early 1960s:

Cities became livable again. Whole communities turned from war zones to nice neighborhoods. We still don't know what caused the great crime drop, but its positive effects are undeniable, and were exhilerating at the time.

It wasn't just crime, either. Health was surging. Life expectancy was

increasing. Smoking was

vanishing. Teen pregnancy was dropping:

Suddenly, the kids were alright.

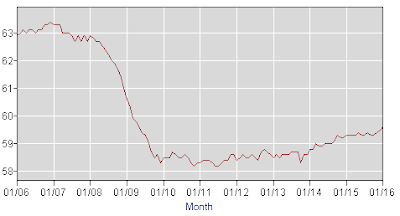

The Economy

In the early 1980s, there were two deep recessions. Unemployment rose and persisted. The middle class spread apart and inequality increased. Everyone said that Japan was eating our economic lunch (yes, competitive corporate nationalism was still a thing back then). The late 80s were a good time, but productivity was still extremely sluggish, as it had been since the early 70s.

Then came the 90s boom. Productivity growth accelerated, and in many industries even

exceeded its postwar heyday. Labor's share of income, which had been declining,

spiked upward. With the addition of a second income, most families became much more materially comfortable. Two or more cars, a sign of wealth when I was a little kid, became the norm. Instead of one small TV, people suddenly had many large and beautiful TVs. Of course, we had computers and the internet as well.

House sizes increased dramatically in the late 80s, then again in the 90s.

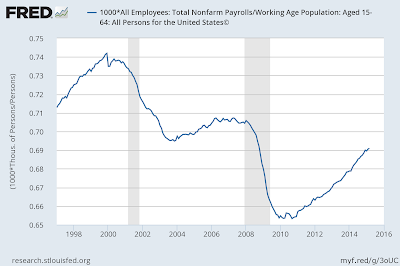

In the late 90s, full employment was reached. Wage growth was rapid. Manufacturing rebounded. Everyone who wanted a job had a job. The stock market absolutely soared. House prices rose. Retirement accounts were flush.

Times were good for the working class, but for the educated class, it was unprecedented party. As a Stanford student in 1999, I didn't even think about what kind of job I was going to get. None of us did, really. People in my dorm were getting rich over the summer on stock they received for interning at Amazon and eBay. It was OK to be a slacker. We all assumed that whenever we got tired of playing video games, we would go out and get rich.

And once again, what mattered most was the sense that this was only the beginning. The end of the Cold War meant that we didn't have to maintain a big military, and the threat of destruction wasn't looming over the markets. Globalization was uniting the world. Technology was changing things in fundamental ways. A.I. and the internet were going to make progress go hyperbolic - it was The Singularity, man!!

We thought we were living in a Vernor Vinge novel. The 20th Century was a long, dark tunnel from which we had finally emerged - the last bloody, terrible trial of humanity as we wrenched ourselves up from our agrarian and animal past into the bright future of peace, freedom, equality, health, riches, and neverending wonder.

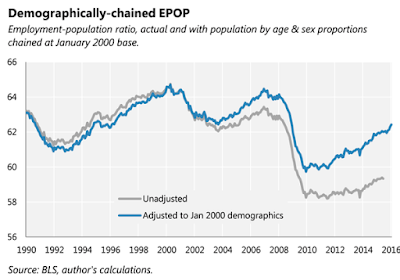

Well, that's how it seemed, anyway. Then we had Bush, Florida, 9/11, the Iraq War, Hurricane Katrina, Putin, the rise of China, Lehman, the Great Recession, years of flat or falling incomes, a resurgent racial income gap, falling female labor force participation, the breakup of the working-class American family, slowing productivity, rising inequality, political polarization, the Tea Party, the heroin epidemic, the alcoholism epidemic, the huge rise in suicide, the end of Pax Americana.

Oops.

Depsite these challenges, the world really is better now in many ways. But it's a darker, grimmer world, at least in America and the other rich countries. Because now we know that although the dreams of the 90s may all still come true, it will be a longer, harder, bumpier road than we had hoped. We have lost the wealth represented by the capitalized value of our extrapolative expectations. We've made progress, but much of our optimism is gone.

That's why I feel like my generation has a duty to the ones that come after us. Because we remember the 90s, we remember what unbounded optimism was like. That optimism doesn't come cheap - you actually have to make the world better if you want to feel the rush of progress. We may be able to get that 90s feeling back, but we're going to have to fight for it.